Saturday, January 27, 2018

A Brief History Of The Bible

The Catholic Church has been know to be the guardian of the Bible, but some say that it added unscriptural books to the Old Testament, namely the Apocrypha.

Actually this is not true. The seven books in question--Tobit, Judith, 1 and 2 Maccabees, Wisdom, Ecclesiasticus, and Baruch are properly called the deuterocanonical books.

The deuterocanonical books are considered canonical (that is, authoritative parts of the Bible) by Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and the Church of the East, but they are considered non-canonical by most Protestants.

The label "unscriptural" was first applied by the Protestant Reformers of the 16th century. The truth is, portions of these books contradict elements of Protestant doctrine (as in the case of 2 Maccabees 12, which clearly supports prayers for the dead and a belief in purgatory), and the "reformers" therefore needed some excuse to eliminate them from the canon. However, these books are "unscriptural" only if misinterpreted. It should also be noted that the first-century Christians--including Jesus and the apostles--effectively considered these seven books canonical. They quoted from the Septuagint, a Greek translation of the Hebrew scriptures that contained these seven books. More importantly, the deuterocanonicals are clearly alluded to in the New Testament.

Finally the canon of the entire Bible was essentially settled around the turn of the fourth century. Up until this time, there was disagreement over the canon, and some ten different canonical lists existed, none of which corresponded exactly to what the Bible now contains. Around this time there were no less than five instances when the canon was formally identified: the Synod of Rome (382), the Council of Hippo (393), the Council of Carthage (397), a letter from Pope Innocent I to Exsuperius, Bishop of Toulouse (405), and the Second Council of Carthage (419). In every instance, the canon was identical to what Catholic Bibles contain today. In other words, from the end of the fourth century on, in

practice Christians accepted the Catholic Church's decision in this matter.

By the time of the Reformation, Christians had been using the same 73 books in their Bibles (46 in the Old Testament, 27 in the New Testament)--and thus considering them inspired--for more than 1100 years. This practice changed with Martin Luther, who dropped the deuterocanonical books on nothing more than his own say-so. Protestantism as a whole has followed his lead in this regard.

One of the two "pillars" of the Protestant Reformation (sola scriptura or "the Bible alone") in part states that nothing can be added to or taken away from God's Word. History shows therefore that Protestants are guilty of violating their own doctrine.

Tuesday, January 23, 2018

Understanding the Origins of Wahhabism and Salafism

The phenomenon of Islamic terrorism cannot be adequately explained as the export of Saudi Wahhabism, as many commentators claim. In fact, the ideological heritage of groups such as al-Qaeda and ISIS is Salafism, a movement that began in Egypt and was imported into Saudi society during the reign of King Faisal.

The official ‘Wahhabi’ religion of Saudi Arabia has essentially merged with certain segments of Salafism. There is now intense competition between groups and individual scholars over the ‘true’ Salafism, with the scholars who support the Saudi regime attacking groups such as al-Qaeda as ‘Qutbists’ (following Sayyid Qutb) or takfiris (excommunicators).

The easy explanation for differences within the Salafi movement is that some aim to change society through da’wa (preaching/evangelizing) whereas others want to change it through violence. But as the Saudi example shows, all strains of Salafism, even the most revolutionary and violent, make a place for social services such as education in their strategies for the transformation of society.

Origins of Wahhabism

When Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab began preaching his revivalist brand of Islam amongst the Bedouins of the Najd [1] during the 18th century, his ideas were dismissed in the centers of Islamic learning such as al-Azhar as simplistic and erroneous to the point of heresy.

Ibn Abd al-Wahhab claimed that the decline of the Muslim world was caused by pernicious foreign innovations (bida’) – including European modernism, but also elements of traditional Islam that were simply unfamiliar to the isolated Najdi Bedouins. He counseled the purging of these influences in an Islamic Revival. Ibn Abd al-Wahhab’s creed placed an overriding emphasis on tawhid (monotheism), condemning many traditional Muslim practices as shirk (polytheism). He also gave jihad an unusual prominence in his teachings. The Wahhabis called themselves Muwahideen (monotheists) – to call themselves Wahhabis was considered shirk.

Origins of Salafism

Salafism originated in the mid to late 19th Century, as an intellectual movement at al-Azhar University, led by Muhammad Abduh (1849-1905), Jamal al-Din al-Afghani (1839-1897) and Rashid Rida (1865-1935). The movement was built on a broad foundation. Al-Afghani was a political activist, whereas Abduh, an educator, sought gradual social reform (as a part of da’wa), particularly through education. Debate over the place of these respective methods of political change continues to this day in Salafi groups such as the Muslim Brotherhood.

The early Salafis admired the technological and social advancement of Europe’s Enlightenment, and tried to reconcile it with the belief that their own society was the heir to a divinely guided Golden Age of Islam that had followed the Prophet Muhammad’s Revelations.

The name Salafi comes from as-salaf as-saliheen, the ‘pious predecessors’ of the early Muslim community, although some Salafis extend the Salaf to include selected later scholars. The Salafis held that the early Muslims had understood and practiced Islam correctly, but true understanding of Islam had gradually drifted, just as the people of previous Prophets (including Moses and Jesus) had strayed and gone into decline. The Salafis set out to rationally reinterpret early Islam with the expectation of rediscovering a more ‘modern’ religion.

In terms of their respective formation, Wahhabism and Salafism were quite distinct. Wahhabism was a pared-down Islam that rejected modern influences, while Salafism sought to reconcile Islam with modernism. What they had in common is that both rejected traditional teachings on Islam in favor of direct, ‘fundamentalist’ reinterpretation.

Saudi Arabia Embraces Salafi Pan-Islamism

Although Saudi Arabia is commonly characterized as aggressively exporting Wahhabism, it has in fact imported pan-Islamic Salafism. Saudi Arabia founded and funded transnational organizations and headquartered them in the kingdom, but many of the guiding figures in these bodies were foreign Salafis. The most well known of these organizations was the World Muslim League, founded in Mecca in 1962, which distributed books and cassettes by al-Banna, Qutb and other foreign Salafi luminaries. Saudi Arabia successfully courted academics at al-Azhar University, and invited radical Salafis to teach at its own Universities.

Saudi Arabia’s decision to host Egyptian radicals hinges on three factors: the need for qualified educators, Faisal’s struggle against Egyptian-led pan-Arab radicalism, and Saudi openness under King Khaled. Between the 1920s and 1960s, Saudi Arabia was emerging as a modern state. Increased oil production required technical infrastructure and a bureaucracy, resulting in a demand for educators that outstripped the administration’s capacity. [2] The Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood represented a source of qualified educators, bureaucrats and engineers, many of them anxious to leave Egypt.

During the late 1950s and the 1960s, the Middle East was gripped by a struggle between the traditional monarchies and the secular pan-Arab radicals, led by Nasser’s Egypt, with the pan-Islamist Salafis an important third force. [3] By embracing pan-Islamism, Faisal countered the idea of pan-Arab loyalty centered on Egypt with a larger transnational loyalty centered on Saudi Arabia. During the 1960s, members of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood and its offshoots, many of them teachers, were given sanctuary in Saudi Arabia, in a move that undermined Nasser while also relieving the Saudi education crisis. [4]

Saudi Arabia’s foreign policy concerns eased in 1970 with Nasser’s death. But in the 1970s, the Saudi education system was awash with Egyptian Muslim Brothers and other Salafis, much as Berkeley was awash with Marxists. Under King Khaled (r.1975-1982), some of the most important proponents of Qutbist terrorism, including Abdullah Azzam, Omar Abd al-Rahman and Muhammad Qutb, served as academics in the Kingdom. Qutb, an important proponent of his late brother Sayyid’s theory, wrote several texts on tawhid for the Saudi school curriculum. [5]

A generation of prominent Saudi citizens was exposed to various strains of Salafi thought during the 1970s, and although most Saudi Salafis are not Qutbist revolutionaries, the Qutbists did not miss the opportunity to awaken a revolutionary vanguard.

Wahhabi-Salafism

Although Salafism and Wahhabism began as two distinct movements, Faisal’s embrace of Salafi pan-Islamism resulted in cross-pollination between ibn Abd al-Wahhab’s teachings on tawhid, shirk and bid’a and Salafi interpretations of ahadith (the sayings of Muhammad). Some Salafis nominated ibn Abd al-Wahhab as one of the Salaf (retrospectively bringing Wahhabism into the fold of Salafism), and the Muwahideen began calling themselves Salafis.

Today, a profusion of self-proclaimed Salafi groups exist, each accusing the others of deviating from ‘true’ Salafism. Since the 1970s, the Saudis have wisely stopped funding those Salafis that excommunicate nominally Muslim governments (or at least the Saudi government), condemning al-Qaeda as ‘the deviant sect’. The pro-Saudis correctly trace al-Qaeda’s ideological roots to Qutb and al-Banna. Less accurately, they accuse these groups of insidiously ‘entering’ Salafism. In fact, Salafism was imported into Saudi Arabia in its Ikhwani and Qutbist forms. This does not mean that the pro-Saudi Salafis are necessarily benign – for example, Abu Mu’aadh as-Salafee’s main criticism of Qutb and Muslim Brotherhood founder Hassan al-Banna is that they claim Islam teaches tolerance of Jews.[6]

Meanwhile, non-Muslims and mainstream Muslims alike use the ‘Wahhabi-Salafi’ label to denigrate Salafis and even completely unrelated groups such as the Taliban.

Conclusions

Faisal’s embrace of pan-Islamism achieved its main objective in that it helped Saudi Arabia to overcome pan-Arabism. However, it created a radicalized Salafi constituency, elements of which the regime continues to fund. It should be kept in mind, though, that this funding is now confined to more compliant Salafis.

Saudi Arabia still has some way to go. Some will say that a leopard can’t change its spots, but in fact the Saudi Government is capable of serious doctrinal change under pressure. Faisal’s broad introduction of Salafi policies involved such a shift, as did the subsequent rejection of Qutbist interpretations of Salafism by pro-Saudi Salafis.

The Middle East today is clearly in need of alternative models of political change to counter takfiri Salafism. In the West, education has been a major factor in social integration. But as the Saudi case study indicates, we need to be aware of not only the quantity, but also the nature of education. Saudi students in the 1970s learned engineering and administration alongside an ideology of xenophobic alienation. In the long run, the battle against violent Salafism will be fought not only on the battlefields of Afghanistan and Iraq, but also in the universities of the Middle East.

Notes

1. A province in the Arabian Desert, now part of Saudi Arabia.

2. Madawi al-Rasheed, A History of Saudi Arabia, Cambridge University Press, 2002, pp122-123. Rasheed observes that most teachers in Saudi Arabia at this time were Egyptians.

3. For a comprehensive account of this struggle, see Abdullah M Sindhi, King Faisal and Pan-Islamism, in Willard L Beling (ed), King Faisal and the Modernisation of Saudi Arabia, London, 1980.

4. Madawi al-Rasheed, p144.

5. Syed Muhammad al-Naquib al-Attas (ed), Aims and Objectives of Islamic Education, King Abdul Aziz University, Jeddah, 1979, p48. Introduction to Muhammad Qutb’s chapter, The Role of Religion in Education. (Proceedings of the 1977 World Conference on Islamic Education, Mecca).

6. Abu Mu’aadh as-Salafee, Exposing al-Ikhwaan al-Muflisoon: the Aqeedah of Walaa and Baraaa’, SalafiPublications.com and As-Sawaa’iq al-Mursalah ‘Alal-Afkaar al-Qutubiyyah al-Mudammirah, SalafiPublications.com, pp48, 50.

Originally published July 15th 2005

Understanding the Origins of Wahhabism and Salafism

Publication: Terrorism Monitor Volume: 3 Issue: 14

By: Trevor Stanley

Democrats Try To Stop The #ReleaseTheMemo Movement On Social Media

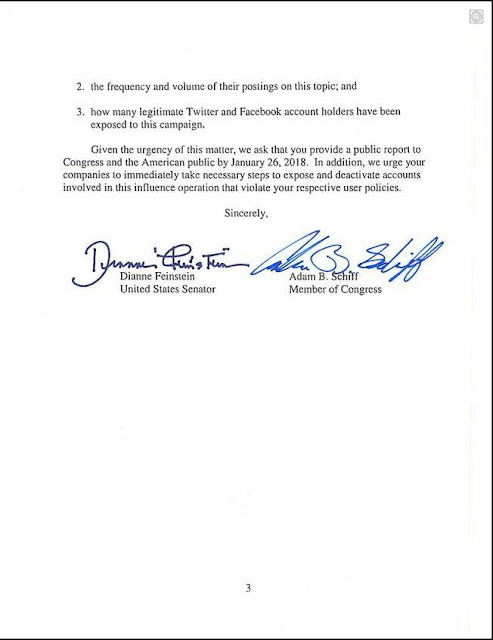

According to Senator Dianne Feinstein and Congressman

Adam B. Schiff, the incredible volume of people on #Twitter & #Facebook typing out the hashtag #ReleaseTheMemo are all a bunch of Russian bots paid by the Trump Administration to sidetrack the Mueller investigation into the Trump/Russian Collusion Farce. So, they wrote this sweet letter to #MarkZuckerberg & #JackDorsey of Twitter asking them to #Shadowban these posts. (See The Letter Below)

House Republicans are hopeful that a four-page memo allegedly containing "jaw-dropping" revelations about U.S. government surveillance abuses will soon be made public.

Rep. Dave Joyce, a Republican from Ohio, told Fox News on Monday that the intelligence committee plans to work on releasing the document but warned that once Americans see it, they’ll “be surprised how bad it is.”

The process of releasing the memo could take up to 19 congressional working days which puts its release around mid-March. The document’s release would first need approval from House Intelligence Committee Chairman Devin Nunes, R-Calif., who can decide to bring the committee back together for a vote. If the majority of the committee votes to release the memo, it would then be up to President Trump.

If he says yes, the memo can be released.

Joyce said he’s personally read the memo twice and “it was deeply disturbing as anyone who’s been in law enforcement and any American will find out once they have the opportunity to review it.”

|

| Feinstien |

Adam B. Schiff, the incredible volume of people on #Twitter & #Facebook typing out the hashtag #ReleaseTheMemo are all a bunch of Russian bots paid by the Trump Administration to sidetrack the Mueller investigation into the Trump/Russian Collusion Farce. So, they wrote this sweet letter to #MarkZuckerberg & #JackDorsey of Twitter asking them to #Shadowban these posts. (See The Letter Below)

House Republicans are hopeful that a four-page memo allegedly containing "jaw-dropping" revelations about U.S. government surveillance abuses will soon be made public.

|

| Schiff |

The process of releasing the memo could take up to 19 congressional working days which puts its release around mid-March. The document’s release would first need approval from House Intelligence Committee Chairman Devin Nunes, R-Calif., who can decide to bring the committee back together for a vote. If the majority of the committee votes to release the memo, it would then be up to President Trump.

|

| Nunes |

If he says yes, the memo can be released.

Joyce said he’s personally read the memo twice and “it was deeply disturbing as anyone who’s been in law enforcement and any American will find out once they have the opportunity to review it.”

Why Do We Support A Terrorist State?

We have been questioning for years why we American's have partned with Saudi Arabia. Saudi Arabia is where the 9/11 terrorists originated from. They are also a brutal dictatorship that lets Wahabbism (false Islam) flurish.

An article in from Political January 2016 reiterates our belief.

Only two Muslim powers remain standing in the Middle East, and suddenly they are on the brink of war. Our old friend, Saudi Arabia, carried out one of its routine mass beheadings last week, and among the victims was a revered Shiite cleric. Our longtime enemy, Iran, which is the heartland of Shiite Islam, was outraged. Furious Iranians burned the Saudi Embassy in Tehran. The next day, Saudi Arabia broke diplomatic relations with Iran.The United States should do everything possible to avoid choosing sides in an intensifying proxy war between the dominant Shiite and Sunni powers in the Middle East. Though history tells us we should tilt toward Saudi Arabia, our old ally, if we look toward the future, Iran is the more logical partner. The reasons are simple: Iran’s security interests are closer to ours than Saudi Arabia’s are.Most trouble in the Middle East emerges from ungoverned spaces—the disputed lands of Iraq, Syria, Palestine, Libya and other countries where many people live beyond the reach of legitimate government. This crisis is different. It pits two stable states against each other.But taking Saudi Arabia’s side would be a disaster. True, militarily the two appear pitifully mismatched. Saudi Arabia is among the world’s best armed states. It has spent vast sums to buy the world’s most advanced war-fighting systems, most of them from the United States. Iran, by contrast, has been under heavy sanctions for decades. Its army is not much better equipped than it was during the Iran-Iraq War 30 years ago.The confrontation becomes equalized, however, when motivation is factored into the equation. Saudis are notorious for their aversion to sacrifice. They hire foreigners to do most of the kingdom’s daily labor. Few Saudi men would dream of risking their lives for their country. For its war in Yemen, Saudi Arabia has recruited hundreds of mercenaries from Colombia. The Saudis have enough air power to devastate almost any country on earth. Wars are won on the ground, though, and there Saudi Arabia is pitifully weak.The Iranians are different. If they believe their faith is under threat, they will pour onto battlefields even if they have to fight with slingshots. That difference in patriotic fervor makes sense. Saudi Arabia has existed for 83 years, Iran for more than 2,500.Saudi Arabia’s decision to provoke this crisis was aimed at least in part at forcing the United States to take sides. Supporting Saudi Arabia over Iran, however, would be a way of harming our own interests.Why does Iran make more long-term sense as a partner? Countries should fulfill two qualifications to become U.S. partners. Their interests should roughly coincide with ours, and their societies should look something like our own. On both counts, Iran comes out ahead.Iran and the United States are bound above all by their shared loathing of Sunni terror groups. In addition, Iran is closely tied to large Shiite populations in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon and Bahrain. It can influence those populations in ways no one else can. If it is brought into regional security arrangements, it will have a greater interest in stability—partly because that would increase its own influence in the region.By almost any standard, Iranian society is far closer to ours than Saudi society. Years of religious rule have made Iranians highly secular. The call to prayer is almost never heard in Iran. In Saudi Arabia, by contrast, it dominates life, and all shops must close during designated prayer breaks. Iranian women are highly dynamic and run many businesses. Saudi women may not even drive or travel without a man’s permission. The 9/11 attacks were planned and carried out mainly by Saudis; Tehran was the only capital in the Muslim world where people gathered spontaneously after the attacks for a candlelight vigil in sympathy with the victims.Turning abruptly away from Saudi Arabia, however, would also be unwise.Both countries have long been hostile to American interests—Iran publicly, Saudi Arabia privately, while pretending to be our friend. Americans have come to understand that Saudi Arabia is a harshly repressive state. Even worse, Saudis are the key financiers of the Islamic State, Al Qaeda, and the Taliban. They sponsor “charities” that build mosques and religious schools where boys in dozens of countries learn to chant the Koran and hate America. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton asserted in a 2009 cable that “donors in Saudi Arabia constitute the most significant source of funding to Sunni terrorist groups worldwide.”Those terrorist groups are America’s principal enemy in the Middle East. Iran hates them even more than we do, since they want to kill every Shiite. Saudis support and promote them. Any policy to address the current crisis must recognize this essential reality.At the same time, however, Saudi Arabia holds one of the keys necessary to unlocking a new future for the Middle East. We can turn that key only by working with Saudi Arabia despite all it has done to undermine our national security. Saudi-bashing is richly justified and emotionally satisfying, but would not be a wise basis for American foreign policy. Precisely because Saudi Arabia has been the principal supporter of abhorrent terror gangs, it has a measure of influence over them. No Christian or Shi’ite Muslim ever will.Anyone who embraces Enlightenment values has reason to detest Saudi Arabia. The fact that it is pouring gasoline over the flaming Middle East is yet another reason. Detesting a country, however, is not reason enough to push it away. Diplomacy has nothing to do with affection. It is about advancing national interests.The United States advanced its interests by reaching a nuclear deal with Iran last year. It will further advance them by building on that agreement to improve relations with Iran. We cannot, however, turn our back on Saudi Arabia, because both countries are the main drivers of sectarian hatred in the Middle East. Some kind of understanding between them is a prerequisite to a calmer Middle East. Encouraging it should be a key goal of American diplomacy. Iran makes a better partner than Saudi Arabia—but we should do whatever possible to avoid having to make that choice

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)